Humanity’s Tale of Loops, Knots, & Thread

— How 200 y/o Crochet Came to be the New Kid on the Block

Crochet is often thought of as a cozy pastime, but it’s actually the youngest member of a very ancient family of crafts. For tens of thousands of years, humans have been twisting, knotting, looping, and weaving fibers. Some techniques became survival tools, others symbols of wealth, and still others pure art. Crochet only entered the picture a few centuries ago, but it carries a legacy stretching back 40,000 years.

Here’s how the story unfolds — step by step.

30,000–40,000 Years Ago: The First Strings

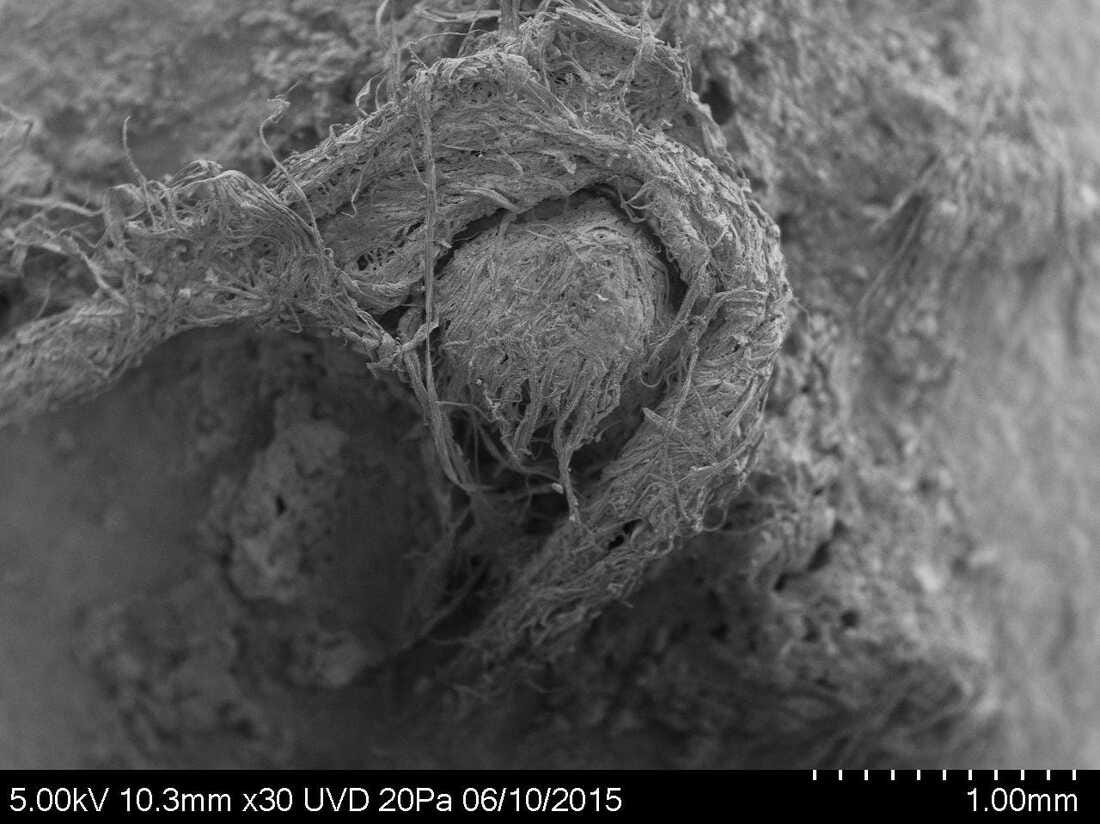

Archaeological discoveries in France and the Czech Republic reveal twisted plant fibers dating back to the Upper Paleolithic. These are the earliest known fragments of string.

Early string was a survival tool: it bound tools, sewed hides, tied snares, and carried loads. In many ways, string was one of humanity’s first technologies.

Tiny bits of twisted plant fibers found on an ancient stone tool suggest that Neanderthals were able to make and use sophisticated cords like string and rope.

This prehistoric piece of string, described in the journal Scientific Reports, was preserved on a flint tool that dates back to around 41,000 to 52,000 years ago. It came from a cave-like rock shelter in southern France that was once inhabited by Neanderthals.

~10,000 Years Ago: Nets and Baskets

Once people had string, they began building with it. The Antrea net from Finland is one of the oldest known fishing nets, found in 1913 in the village of Korpilahti on the Karelian isthmus in Antrea, then in Finland but now belonging to Russia. It is dated to 8540 BCE. The net is made out of willow and it is estimated -- based on the number of parts found -- to have been roughly 89 to 98 ft long by 4 ft 3 in – 4 ft 11 in wide, with a 2.4 in mesh. The size of the mesh is suitable for fishing salmon and common bream.

String was also looped and woven into baskets, mats, and traps. Net-making shows how humans engineered string into tools that sustained entire communities.

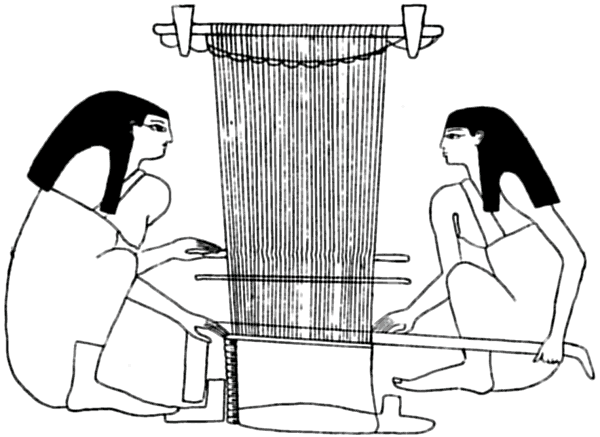

~7,000–5,000 Years Ago: Weaving Looms

In Mesopotamia, Egypt, and South America, weaving looms appeared. Woven textiles began to replace hides and felt.

Weaving carried meaning beyond utility: cloth became a marker of cultural identity, a form of tribute, and a commodity in trade.

Bronze Age Onward: Sprang

Another early technique, sprang, appears as far back as the Bronze Age. Instead of weaving over and under, sprang interlinks warp threads, creating stretchy, net-like fabric.

Sprang was used in ancient Egypt for hairnets and in Northern Europe for belts, bags, and sashes. It bridges the gap between net-making and weaving, showing yet another way humans experimented with string.

~2,000–3,000 Years Ago: Nålbinding

Before knitting, there was nålbinding — an ancient looping craft found in Scandinavia, the Middle East, and Africa.

Made with a single large needle and short lengths of yarn, nålbinding produces dense, durable fabric. Unlike knitting, it doesn’t unravel easily. Surviving socks and mittens show its practical role in cold climates more than 2,000 years ago.

~1,000–1,500 Years Ago: Knitting

Knitting — using two or more needles to create stretchy, continuous loops — appears around the 11th century, with examples from Egypt.

By the Middle Ages, knitting had spread across Europe, producing stockings, caps, and gloves. Knitting guilds made it a professional trade, while at home it remained a practical family skill.

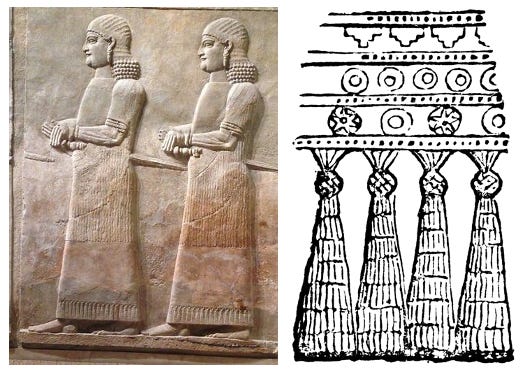

13th Century: Macramé

As weaving traditions evolved, Arabic weavers developed macramé — decorative knotting added to the fringes of woven cloth to keep it from fraying. The word itself comes from miqramah, meaning “fringe.”

Sailors adopted macramé, spreading it across the seas. They used knotting for hammocks, belts, and decorative fringes during long voyages. By the Renaissance, macramé had reached Europe, where it appeared in Italy, France, and Spain.

Macramé resurfaced in the Victorian era for home décor, and in the 1960s–70s it boomed alongside crochet in the counterculture movement. Today, it thrives in modern “boho” décor, with plant hangers and wall art keeping the tradition alive.

15th–16th Centuries: Bobbin Lace

In Italy and Flanders, artisans developed bobbin lace. Dozens or hundreds of threads were wound on bobbins, crossed and twisted over a pillow, and pinned into intricate patterns.

Bobbin lace adorned collars, cuffs, and church vestments. It was exquisite and costly — a craft of the elite. For everyday families, it was out of reach.

17th–18th Centuries: Tatting

From decorative knotting traditions came tatting, a lace-making method using a shuttle or needle to form rings and chains of knots.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, tatting was popular for trimming linens and clothing. It often appeared in the same pattern books as crochet, reflecting their shared role in affordable lace-making.

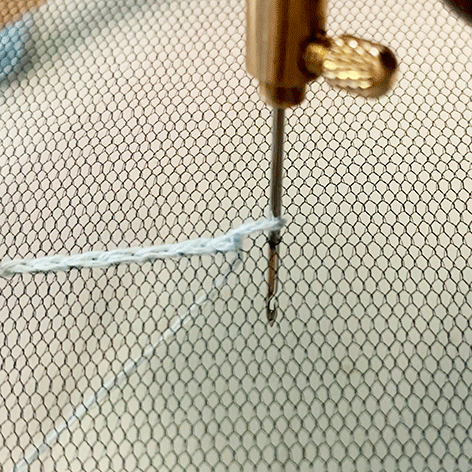

18th Century: Tambour Embroidery (The Hinge to Crochet)

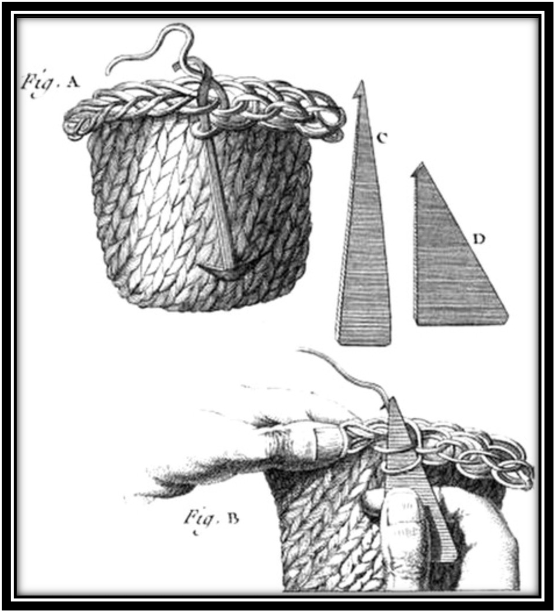

Tambour uses a hooked needle to make chain stitch on fabric. This technique spreads through Asia and the Middle East into Europe. It is the mechanical and conceptual pivot: once the hook leaves the fabric and the chain continues in the air, we’re essentially crocheting.

Early 19th Century: Shepherd’s Knitting

Before “crochet” becomes the standard term in English, hooked wool work is often called Shepherd’s Knitting (worked with a “shepherd’s hook”). It yields a dense, practical fabric and is associated with rural, working communities.

Early English references (e.g., Elizabeth Grant’s Memoirs of a Highland Lady, reflecting 1812 experiences) describe garments made with a hooked tool, while 1830s–1840s publications begin normalizing the word “crochet.” Shepherd’s Knitting marks the transitional phase from hook-on-fabric (tambour) to free-loop hooking in yarn.

18th–19th Centuries: Crochet Emerges

Crochet likely developed from tambour embroidery, which used a hooked needle on fabric. By the late 18th century, the hook moved off the fabric, creating free-loop crochet.

In the 19th century, crochet spread rapidly across Europe and the Americas. For the wealthy, it made lace accessories. For working families, it meant shawls and blankets. During the Irish famine, crochet lace became a survival craft, providing income for families who sold their work abroad.

Crochet entered the world as both practical and beautiful, a craft open to anyone with a hook and thread.

Are Any of These Crafts Dead?

Not at all. Every one of these traditions is still alive today — though some thrive in smaller, specialized communities:

Nålbinding is practiced by heritage groups, reenactors, and enthusiasts in Scandinavia and beyond.

Sprang is taught by niche weaving guilds and experimental archaeologists.

Bobbin lace and tatting are practiced by dedicated guilds worldwide.

Macramé has gone through repeated revivals, with another boom in today’s home décor market.

Knitting and crochet are global giants, with thriving online and offline communities.

Weaving and net-making remain both functional and artistic, sustained by traditional cultures and modern makers alike.

Rather than disappearing, these crafts have adapted — shifting from survival tools or elite fashion to cultural heritage, niche art forms, or global creative movements.

Today: A Living Family of Crafts

Crochet now lives alongside its older relatives.

Each represents human ingenuity in turning string into structure. Crochet, however, stands out for its accessibility and adaptability. In the 21st century, it’s gone beyond fashion and home goods into mathematics, art installations, and online communities.

When you pick up a crochet hook, you’re not just practicing a craft. You’re holding the latest link in a chain that stretches back 40,000 years — the story of how humans, across time and place, turned simple string into beauty, survival, and connection.

Want to know more? Listen to the Exploration Crochet Podcast - Crochet Through Time: The New Kid on the Block